The attraction continues into investment where including an allocation to gold in an investment portfolio has been justified by its somewhat unique attributes. It is a proven safe-haven asset; a reliable store of real value over time. Its finite supply and historical role as a form of, or backstop to, currencies has explained its use as a hedge against inflation and currency depreciation, preserving purchasing power when fiat currencies weaken.

This, together with its correlation characteristics against traditional assets including stocks and bonds, can make gold an attractive risk management tool. Its global demand and performance during (or often ahead of) crises further enhances its appeal. With historical returns outpacing inflation, gold presents investors with a potential way to store their accrued wealth that has stood the test of time.

In this article, we explore the benefits and challenges of holding gold in an investment portfolio. We look at its monetary premium, how it can provide protection against currency depreciation and its role as a safe-haven / risk-hedging asset. We look at how gold has performed historically and ways in which investors can gain access to this asset class, such as newer investment wrappers like tokenisation. These are effectively gold-backed investments structured and traded on a decentralised digital record-keeping system that’s run by a network of computers.

What do we mean by ‘monetary premium’?

The monetary premium of an asset refers to the additional value that it commands beyond its practical or industrial value. This is driven by its perceived role as a store of real wealth; for example, where risk-free interest rates are lower than realised inflation, other higher yielding assets can seem attractive. This has been the case for decades in property prices. In the case of gold, its role as a store of value arises from its scarcity (the global supply of gold increases by only around 1.6% p.a.)1, tangibility and historical acceptance as a medium of exchange and store of value. Unlike fiat currencies, which can lose real value due to increased money supply,2 gold’s monetary premium reflects its historical ability to retain purchasing power value, appealing to investors seeking long-term wealth preservation.

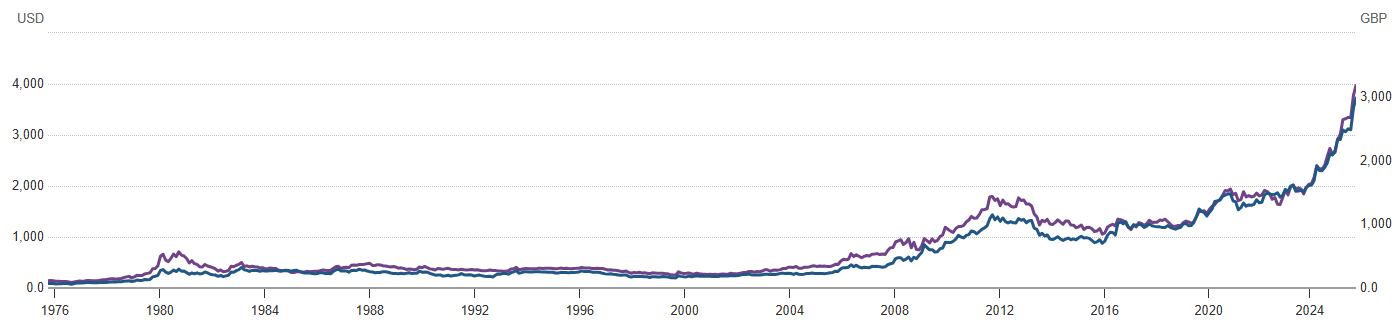

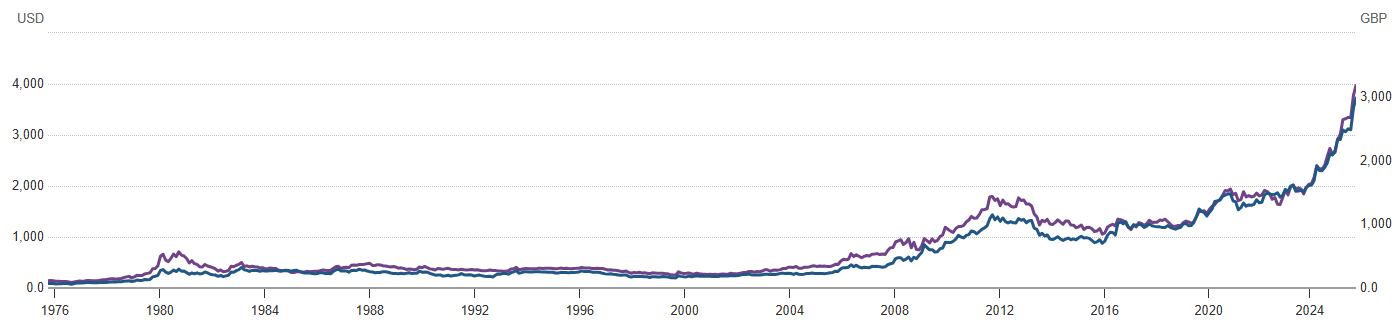

Gold price per ounce in USD (purple line) and GBP (blue line) September 1975 – September 2025

Source: Gold Spot Prices & Market History | World Gold Council

The chart above show the appreciation of gold over the long term, clearly demonstrating its ability to preserve wealth throughout economic cycles, wars, times of high inflation and changing political regimes. It also shows, however, the volatility of returns exhibited by this asset class (in both USD and GBP). Indeed, gold prices were subject to a significant overall decline between 1980 and 1999 and it wasn’t until 2008 - 28 years later - that gold was back up to its 1980 high. This was in stark contrast to the equity market, which rose significantly over the period; the FTSE All-Share Index delivering a compound annual growth rate of c.14% p.a.3

This extended bear market for gold was influenced by a merging of economic, monetary and market factors, which had the effect of reducing its appeal. One could argue that equity became the monetary premium investment asset of choice during this period due to a combination of factors. Factors such as prevailing monetary policy, declining inflation, central bank gold reserve sales, sustained momentum in the stock market, global demographics and improved economic optimism during the period.

The way in which some of these factors influence the price of gold are relatively intuitive. For instance, high interest rates that make yield-bearing assets, such as bonds and savings accounts, more attractive than non-yielding gold; but the relationship between money supply and gold may be less well understood.

Money supply and the price of gold

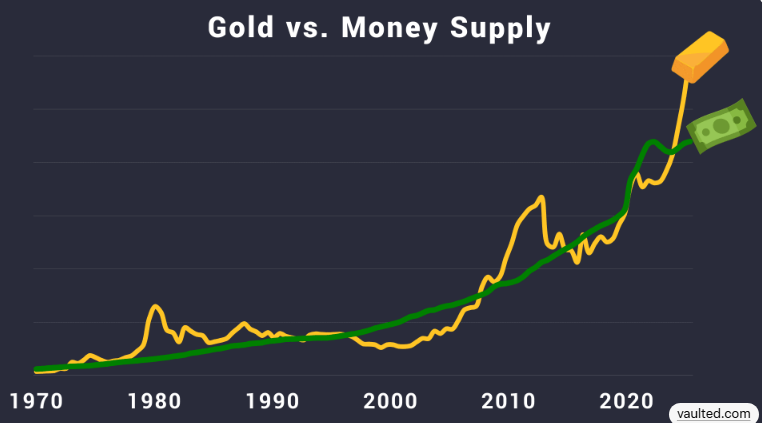

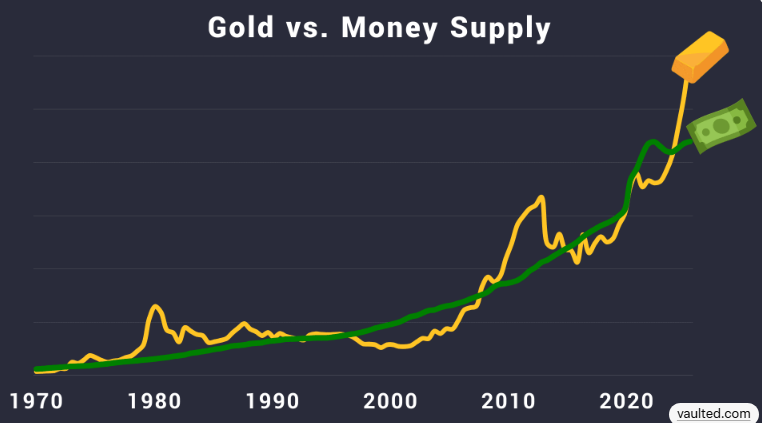

History has shown that the price of gold tends to rise when a country’s money supply grows faster than its economic output. This is because printing more currency (such as pounds or dollars), without matching growth in goods and services, dilutes the value of that currency. This dilution reduces the purchasing power of each unit of currency in circulation. In contrast, gold is a finite asset, which cannot simply be printed. So during periods of looser monetary policy and increased money supply, investors might buy gold to preserve wealth, driving up its price in that currency. This is shown in the chart below, which illustrates the correlation between the price of gold and money supply. The correlation is not perfect, however: money supply grew steadily between 1980 and 1999 while overall gold prices declined. This may be due to the impact of the other factors identified earlier.

Source: Vaulted.com

So, if we expect the money supply to continue to grow as it has been over past decades, then holding gold within an investment portfolio may prove to be a wise investment decision in the longer term, unless other assets take its place.

Protection against Sterling depreciation and historical performance

Gold has been a timeless and universal money. History is the proof; since 1750, about 80% of all currencies have disappeared and the other 20% have all been severely devalued.4

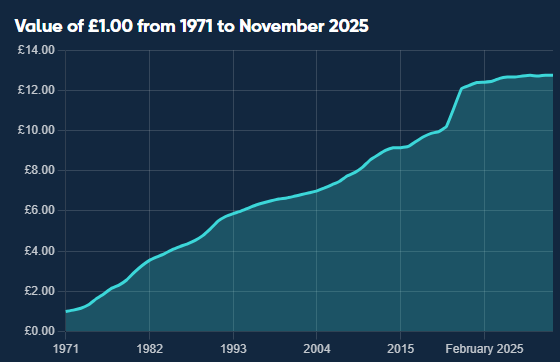

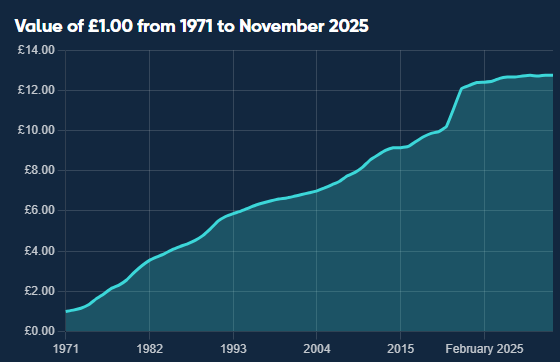

Indeed, the British pound (Sterling) has faced significant depreciation over time, particularly since the end of the gold standard in 1971. Its purchasing power eroded by inflation. You would need £12.75 in November 2025 to have the same purchasing power as £1.00 in 1971!

Source: Inflation calculator | Bank of England (https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator)

Meanwhile, the Sterling price of gold has increased commensurately during this time. Indeed, between 2000 and 2020 the price of gold in nominal Sterling terms rose by approximately 500%,5 far outpacing inflation. Gold has therefore served as an effective hedge against fiat currency depreciation.

Over 2025, the price of gold rose by c.60%. This raises a question to what degree this protection against inflation will continue, not least over the short to medium term. As with any investment, the time horizon of exposure matters: when you buy, when you sell and how long you hold the asset for.

Allocating a proportion of assets to gold

Historically, pension schemes have tended not to invest in gold; A typically advisor-led decision, but why? The answer can partly be attributed to gold’s lack of tangible regular income generation. Unlike many so-called ‘traditional assets’, such as stocks and bonds, gold does not pay regular dividends or interest. This makes it more difficult to objectively value in the traditional sense. Income generating assets are typically and increasingly preferred by schemes, which require steady cash-flows in order to meet liabilities – i.e. to pay pensions. Instead, gold's value relies entirely on price appreciation, and while this has been significant over long periods, this can be volatile and seemingly unpredictable. This has led gold to be perceived as a ‘riskier’ asset choice.

In addition, it’s important to understand that, in the case of gold, one ounce of gold is a constant (i.e. it is fixed and does not fluctuate) whereas the value of currency, for example one pound Sterling, is not. Therefore, when we see the Sterling price of an ounce of gold go up, this is simply reflecting the fall in the value (i.e. the purchasing power) of pound sterling. In addition, the monetary premium ebbs and flows between gold and other assets such as equities and property, and this also results in valuation changes.

Behavioural science also plays a part to the extent that investors exhibit, amongst other things, familiarity bias: preferring traditional assets over gold's "alternative" status. As well as herd mentality: where portfolios are constructed in such a way as to replicate those put in place by peers in order to reduce career risk. And finally loss aversion: when investors seek to avoid shorter term price movements.

Despite this, however, gold has demonstrated that over a long period it can be useful in offering real portfolio value protection in times of economic stress and uncertainty. Adding gold into the asset mix could lead to improved portfolio performance over the long term. Indeed, research carried out by the World Gold Council in 2023 highlights that many pension holders would welcome gold as part of their pension pot, suggesting that this asset has the potential to play a far greater role in UK pension funds.

So, how might gold be incorporated into an investment portfolio?

A key consideration relates to the extent to which gold might be used as a diversification asset and the correlation between the returns delivered by gold and other asset classes over time:

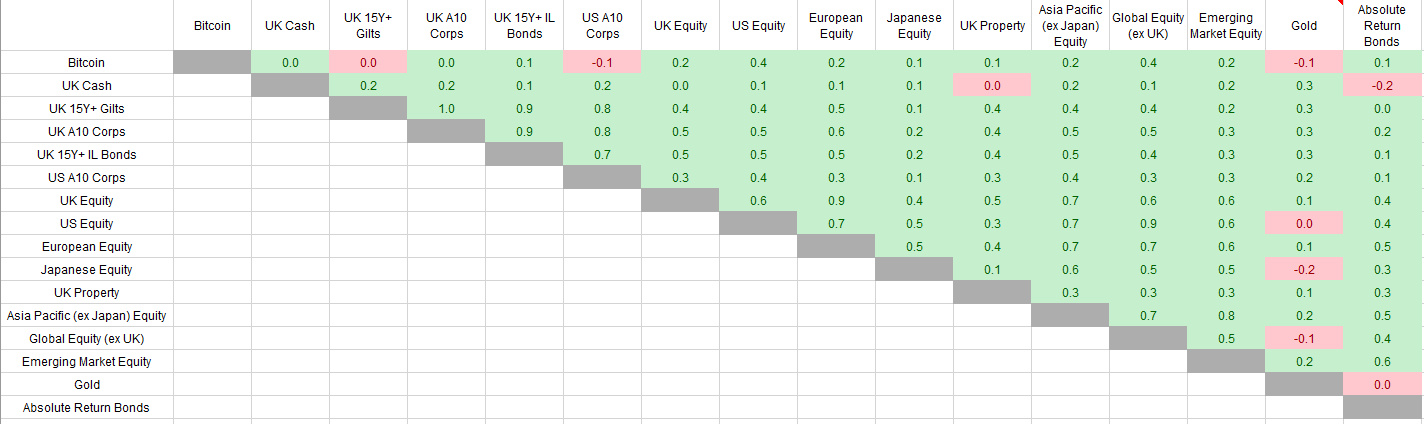

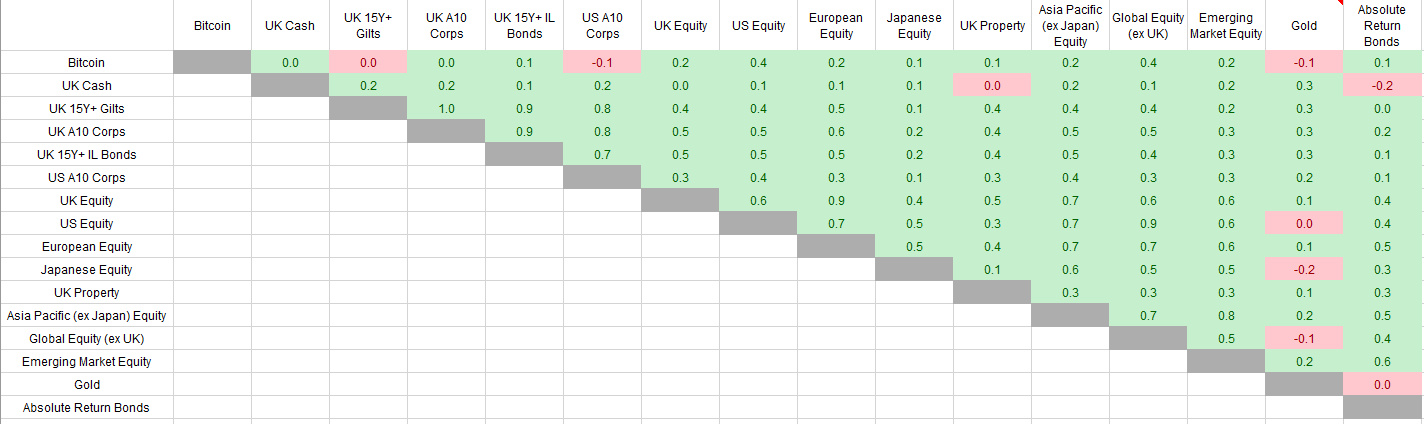

Five-year monthly correlation matrix

Source: Refinitiv, Cartwright

The matrix above shows the correlation between gold and other asset classes over the last year. It shows that gold has had a low / negative correlation with many of the traditional asset classes over this period. Historically the correlation between gold and equities has often been negative during times of economic stress. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, gold prices surged whilst equities were negative.

A further consideration relates to how much should be allocated to this asset class. This all depends on the specific circumstances of the investment portfolio, as well as the degree to which it is able to withstand volatility over the investment period.

Studies carried out by the World Gold Council and CFA suggest an allocation of c.5% may help to create a more balanced and stable portfolio, but of course the optimal allocation will also depend on the way in which the rest of the portfolio is invested.

Environmental, social and governance implications of investing in gold

Increasingly, investors are giving consideration to the environmental, social and governance (ESG) impact associated with the investment of any and all assets, and gold is no different. From an environmental view point, the mining of gold is energy intensive, creates significant carbon emissions and may damage ecosystems. In addition, the processing of gold and waste management often relies on chemicals, which can cause long-term ecological harm.

From a social and governance point of view, labour conditions are often cited as a key consideration; mining can involve safety risks for workers while community relations and the need to respect Indigenous rights are also important. Governance issues such as corruption, transparency, and supply-chain traceability also matter, with responsible investors preferring to invest in gold that is ethically sourced.

Investors must therefore evaluate the ESG aspects of investing in gold beforehand, in order to help reduce long-term reputational and operational risks and ensure that gold exposure aligns with sustainability principles.

Vulnerability to the new kid on the block

Bitcoin has been referred to as digital gold. Whilst this is not a perfect analogy, it is a good starting concept. Bitcoin has some advantages over gold, such as being cheap and quick to send over the internet in payment. Gold has some advantages over bitcoin, such as its 5000-year history providing greater familiarity and acceptance.

Over time, bitcoin’s fixed and easily verifiable supply cap is a powerful advantage over gold’s uncertain and growing supply. However, this advantage may take many years to manifest. In the meantime, both assets are likely to perform well and some clients may wish to combine both within an allocation so that each provides diversification against the other.

Accessing exposure to gold

The ways in which investors can gain exposure to gold are plentiful. We explore some of these below:

1. Physical gold

Physical gold, such as bars or coins, offers direct ownership and is typically stored in secure, insured vaults managed by custodians. This method provides tangible security and protection against crises but is associated with storage costs, liquidity constraints and regulatory compliance implications.

2. Gold securities

Investing in gold mining stocks may provide a degree of exposure to gold price sensitivity, however this is not the same as owning gold and the risk and return characteristics of the two are very different.

Gold securities may be associated with operational leverage, which can result in gold stocks outperforming gold during bull markets and vice versa. They are also associated with equity risk – company debt levels, operational costs, company specific risks to name but a few – which mean that gold stocks can be more volatile than actual gold.

3. ‘Paper gold’

The term ‘paper gold’ refers to financial instruments that provide exposure to the price of gold but without investor ownership of physical gold. These instruments track or represent gold value on paper (contracts, shares, or claims), rather than being backed by gold you personally own. Paper gold includes gold exchange traded funds and gold futures contracts.

‘Paper gold’ may present a convenient way to access the asset class, however it is also associated with counterparty risk. This is because you rely on a bank, broker or exchange holding the gold or fulfilling the contract. It also has redemption restrictions and tracking errors whereby the price of paper gold lags behind the spot price of physical gold.

4. Tokenisation and asset-based gold investments

Tokenisation and digital asset technology offer a new way for investors, including pension schemes, to invest in gold by digitising ownership backed by physical gold. These methods combine the benefits of physical gold with the liquidity and efficiency of digital assets but are also associated with counterparty risk.

Final thoughts

For many investors, it’s worth considering whether incorporating gold into an investment portfolio can offer a potential route to real wealth preservation. Alternatively, as a hedge against a broad market sell off (e.g. a widespread monetary premium unwind in traditional markets), or improved portfolio diversification and therefore increased portfolio efficiency. Over certain timeframes, gold - whether through physical bullion, gold securities, or tokenised assets - can provide stability in the face of inflation, currency depreciation and economic uncertainty.

Whether or not gold is attractive for an individual investor, what is certainly the case in our opinion, is that the risk of a broad based monetary premium unwind should be added to an investors risk register as a high impact event. Moreover, the likelihood of such a risk should be explicitly considered.

Sources

1. World Gold Council Gold Demand Trends reports and related data releases as of October 2025, global supply of gold defined as the total above-ground stocks of all gold ever mined.

2. Money supply refers to the total amount of money available in an economy at a particular point in time and can be measured using the following categories: M1: The most liquid forms of money — currency (coins and paper money) held by the public plus demand deposits (checking accounts) and other checkable deposits. M2: Includes everything in M1 plus savings deposits, small deposits, and money market mutual funds — forms of money that are slightly less liquid. M3: (used in some countries): Includes M2 plus other large deposits and currencies; essentially a broader range of liquid assets

3. Tickerfunds.com

4. Source: https://x.com/RayDalio/status/1979221211188998472

5. Source: Macrotrends.net Gold Prices - 100 Year Historical Chart